The unequal response to COVID-19 is a recipe for global failure to control the pandemic.

Introduction

Caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is one of a kind in 100 years since the Great Influenza pandemic or Spanish flue of 1918. Economies have been devastated and Health systems shaken to the core across the world. Nevertheless, it has not all been bad news with the pandemic as we have seen unprecedented roll out of innovations, uptake of digital technologies, and for the first time in the history of vaccinology i.e., vaccine ready for clinical use in one year of its design.

Countries have raced at different speeds to provide solutions for their people. As I write, UK and USA have vaccinated over 70% of their adult population with at least one vaccine dose while most limited resource countries have not even vaccinated 1% of their adult population. The default control approach globally has been lockdown to reduce the transmission of the virus. Lockdowns are devastating to mental health, education, and economies overall and are thus not sustainable. They should be temporary and only a transition to regain public health control of the disease.

High income countries (HICs) have been at the forefront of COVID-19 testing, surveillance and vaccination which is now paving the way to make lockdowns history in these countries. As stated by several speakers during the COVID-19 pandemic, “no one is safe until everybody is safe”. This means the HIC success is futile if the rest of the world is still on ‘fire’ generating new variants of SARS-CoV-2 virus. In this blog I highlight the unequal global response to COVID-19 and the critical need to support low- and middle- income countries to manage the pandemic as they scale up their vaccination rates.

The imbalanced response to COVID-19 and the way forward

By April 2020 all academic experts in UK were soul searching looking out for ways they can help the fight against COVID-19 pandemic. I joined the COVID-19 Clinical Research Coalition (https://covid19crc.org) to provide my expertise on the Virology, Immunology and Diagnostics (VID) working group. Our working group was tasked with identifying ways and means to standardise COVID-19 testing and biobanking samples needed for diagnostics and vaccines research.

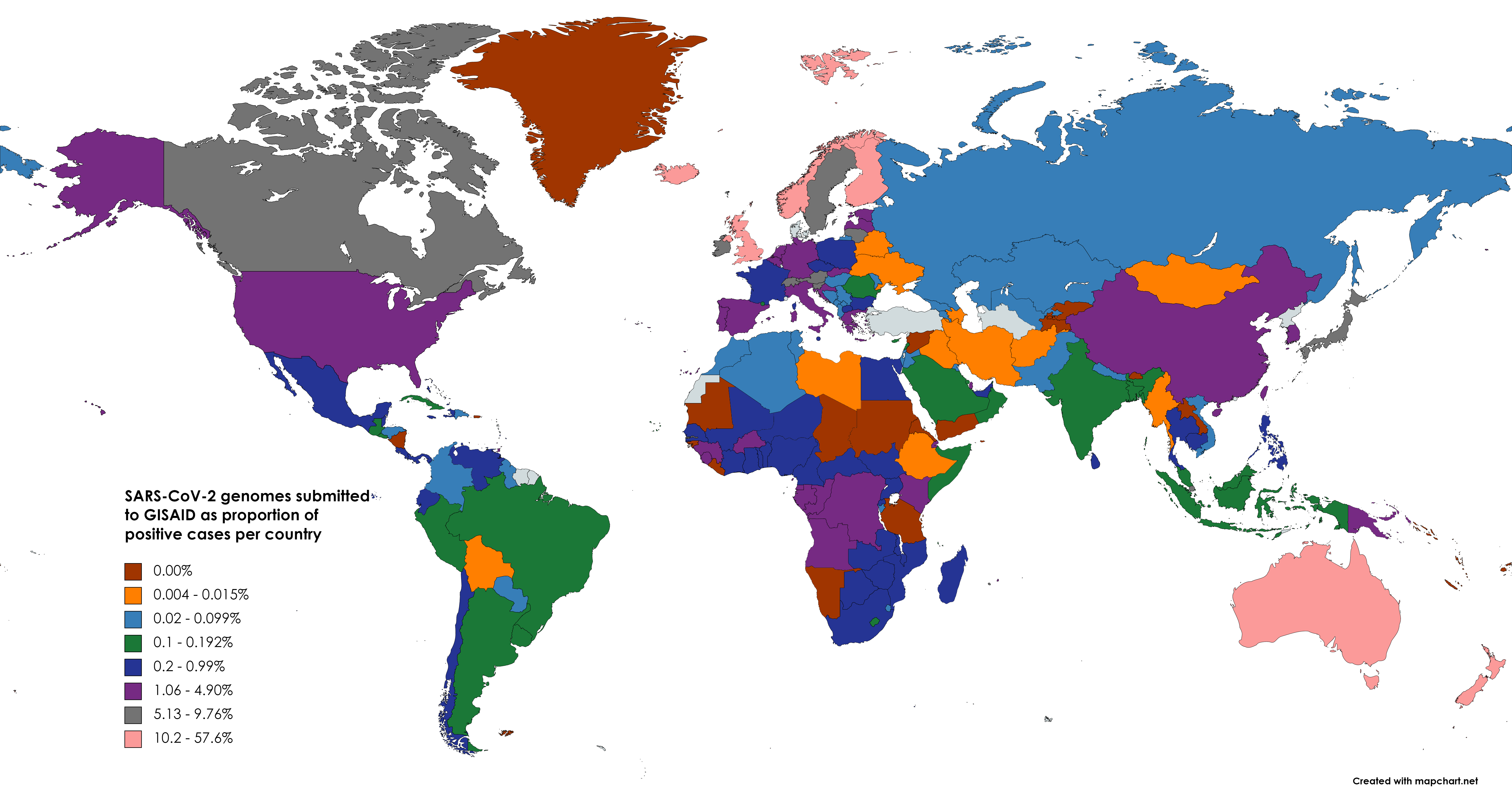

In the 2nd quarter of 2020, many fundamental questions were being asked such as what the infective dose of coronavirus vis-à-vis the quantification cycles of the PCR test is, sample type to test (sputum, saliva, oropharyngeal or nasal swab), how accurate are antigen and serological tests etc. Sequencing of the SARS-CoV-2 genome was going on in some countries, but it was not clear what proportion of samples should be sequenced to ensure effective surveillance and detection of emerging variants. Lockdown and social distancing were the main public health tools available because testing and isolating all the infected people with or without symptoms had proved impractical even for the HICs. Fast forward, today some countries have capacity to test tens of thousands per day with both PCR- and antigen-based tests and have vaccinated over half of their adult population while most low- and middle- income countries have not vaccinated 1% of their vaccine eligible population and are unable to test everyone who needs a test. This imbalanced success leaves the world vulnerable to emergence of potentially more lethal COVID-19 variants, Figure 1.

Figure 1: COVID-19 whole genome sequencing map showing number of genomes as proportion of COVID-19 cases per country submitted to the GISAID database. The low testing capacity in LMICs exaggerates the proportion of COVID-19 sequencing done, e.g., USA 775K genomes/36.9 million cases = 2.1% compared to DRC 629 genomes/53K cases = 1.2%.

The UK is one of those countries that have been at the forefront of using evidence to guide COVID-19 response. By April 2020, COVID-19 Genomics consortium UK (COG-UK) had been convened and funded with £20 million to perform large scale whole genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2. The fruit of this investment was the early detection of the Kent COVID-19 variant later known as UK variant B.1.17. This example was soon followed by South Africa, Brazil and more recently India where variants of concern, B.1.351, P.1, and B.1.617.2 were respectively identified[1]. The variants first described in UK and India have been by far the most epidemiologically successful having spread to almost every country in the world. More so for the B.1.617.2 (delta) variant that has caused infections in both vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. The recent USA Massachusetts outbreak where 74% of the cases were fully vaccinated demonstrated the ability of the variants to break through and cause infections[2]. The good news so far is that very few fully vaccinated individuals are requiring hospitalisation and in the Massachusetts case none of the vaccinated people died of the disease. The vaccines seem to be holding up though reports are emerging of break through severe infections and deaths.

Important to note, however, is that detection of new SARS-CoV-2 variants has not always been followed with rapid response at national and international levels. Recognition of a variant and its gravity goes through stages i.e., variant of interest (VOI) then variant under investigation (VUI) and by the time it gets to the variant of concern (VOC), it is already spread widely in the population. The reasons for the delay are scientifically understandable: first, the variant is detected in a few cases and thought to be a one off or localised case, secondly, there is no knowledge about how transmissible and virulent the variant may be, and more importantly on its impact on the available vaccines. These questions take time to answer but the virus doesn’t stop and wait till we know what do with it. So how can we be proactive and act more quickly?

- Conduct routine and consistent whole genome sequencing of the virus: this will ensure that variants are detected early, potentially closer to the index case from whom the variant emerged before infecting many people.

- Take the variant serious by conducting comprehensive contact tracing to ensure the potential victims are identified, tested, and isolated if positive.

- Immediately study the impact of the variant on immunity: This is where systematic sampling and preservation of specimen (serum, plasma, whole blood etc) from previously infected and vaccinated people is crucial to ensure rapid testing of emerging variants. Waiting to investigate the natural course of infection in the population is too late for highly transmissible variants.

- Vaccinate and vaccinate to limit space and time for the virus to evolve into new variants.

It is important to note that most low- and middle- income countries (LMICs) are not anywhere near achieving the implementation of a) to d) above. The dangerous resort is to say, ‘for us we are sorted, let them sort themselves’. COVID-19 knows no borders; it will soon return to the doorstep of those who think they are sorted, and the effects will be more disastrous, potentially erasing the achievements made with the current vaccines globally. To avoid this scenario, countries and corporations who have means are obliged to support LMICs to develop COVID-19 testing and surveillance capabilities. In the meantime, LMICs can respond by doing everything they can to expand testing, surveillance, implementation of infection prevention and control measure and ensuring proper recording of COVID-19 incidence, morbidity, and mortality. Finally, vaccine manufacturers and Intellectual Property owners must allow establishment of more plants across the continents to manufacture generic vaccines and ensure supply meets the demand.

The world must work together to avoid failure to globally control the virus. Once again, “no one Is safe until every is safe”.

[1] European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2021) SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern as of 29 July 2021. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/variants-concern Accessed 6th August 2021

[2] Berkeley Lovelace Jr (2021) CDC study shows 74% of people infected in Massachusetts Covid outbreak were fully vaccinated. CNBC Health & Science Friday July 30th 2021. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/07/30/cdc-study-shows-74percent-of-people-infected-in-massachusetts-covid-outbreak-were-fully-vaccinated.html Accessed 5th Aug 2021